Summary

nstftp consisted basically on reverse-engineering a custom network protocol (on the application layer) via a .pcap file with recorded interactions between a custom FTP client and server (hence the “ftp” in the name “nstftp”), and then creating a client that knows how to talk to that server to recover the original FTP server program to finally reverse-engineer it and find a dev-made backdoor to print the flag for us from the remote machine * breathes *. Piece of cake… right?

Intro

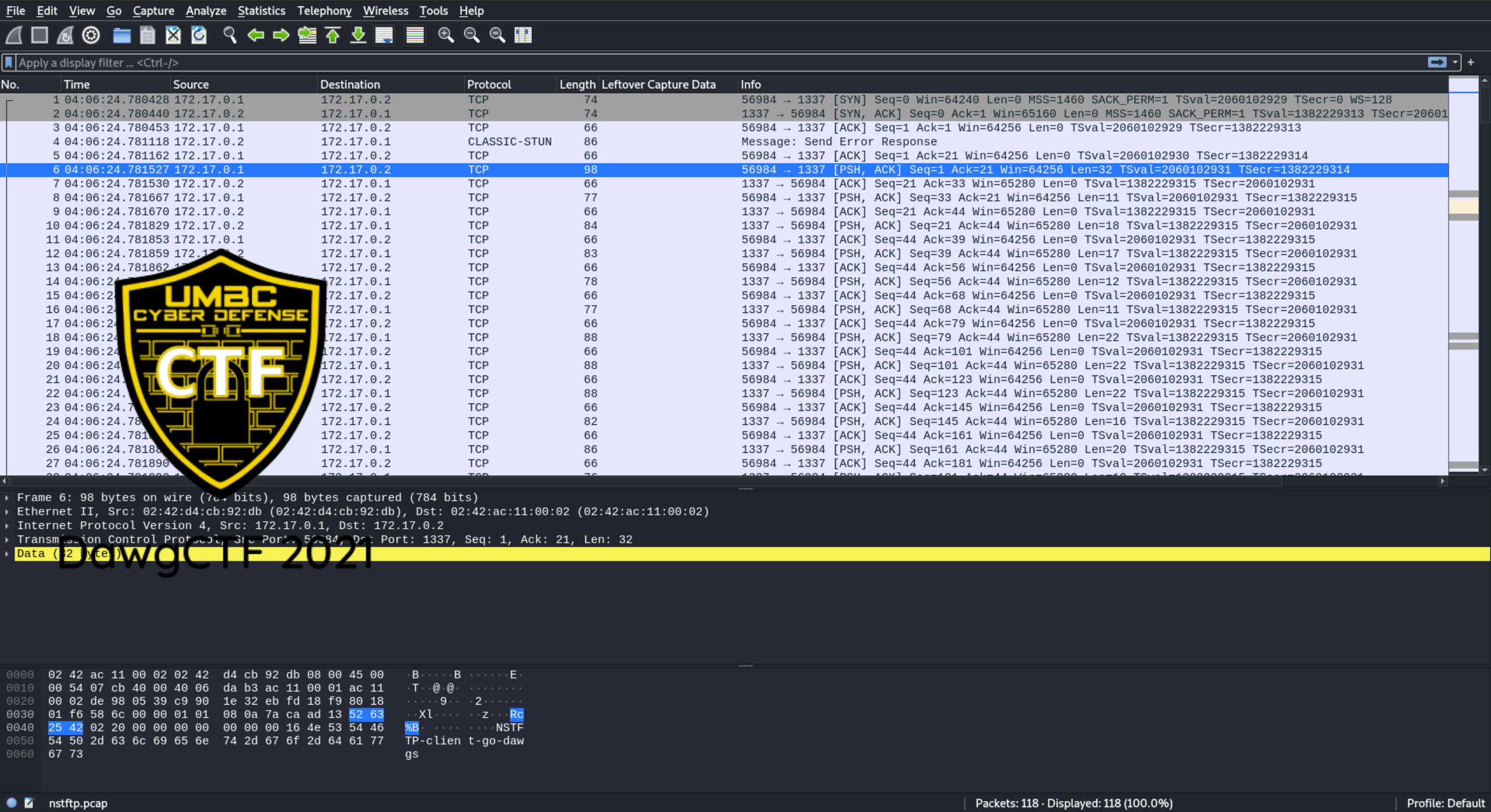

Welcome curious readers, some days ago DawgCTF took place, with 595 different teams competing on a “Jeopardy” style CTF featuring “Pwn”, “Reversing”, “Binary Bomb” (?), “Crypto”, “Audio/Radio”, “Fwn (Forensics/Web/Network)” and “Misc”. This event was hosted by the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), and it was a really good experience overall, although some lack of sleep took out the best of me and I ended up spending lots of hours on this chall until late at night.

Anyway, let’s go with the chall description:

A repo with the challenge’s files can be found here (so you can follow up if you’d like).

First Look

Looking at this the first time I really wanted to know where the meaningful data could be hiding in plain sight, as there were already too few packets in the .pcap and also some weird error messages on a UDP protocol I’ve never heard of (CLASSIC-STUN), but I was also asking myself: what kind of software could we be looking at? So with nothing else to do I started inspecting packet-by-packet from start to finish, hoping for the best and just waiting for any ray of sunlight to struck me.

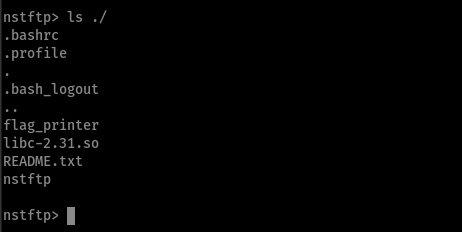

Soon, I realized that the “data” section of many TCP packets had some ASCII strings on them by the end of their data sections, but more interestingly, some common Linux file names on them: ., .., .profile, .bashrc and .bash_logout; along with the other files: flag_printer, libc-2.31.so, nstftp and README.txt.

The client was sending something to the server that made it respond with some file names. This was oddly familiar to a remote ls on a user’s home dir, but the server was also sending back some file’s contents…

That’s when hit me like a bug in a windshield: this was a simple FTP client retrieving files from the remote machine.

Now the other files made sense, the challenge was just making a custom FTP client to gently ask the server to give us the flag_printer file, which would then make our flag after being executed (and probably after passing it a password - you know, the classic rev challenge), right?

Reversing The Protocol

This sounded really interesting on itself, as making protocol specifications is not that trivial because it requires some answers to questions being cleared before-hand: “how does the client starts communicating with the server? (hello phase)”, “how does the client/server know how many bytes to wait for when they’re talking”, “how do we order or command the server to do something? should it be with (already known) numbers, strings, etc?”, “is there any way to check for communication errors? if so, how do we deal with those?”, along many more. So I really wanted to know which was the length for which the challenge makers went to make this 400 points chall.

Naturally, our first steps in this was to try to answer most of those “protocol’s spec” questions, in order to get some insight for a functional client program that tries to comply with it.

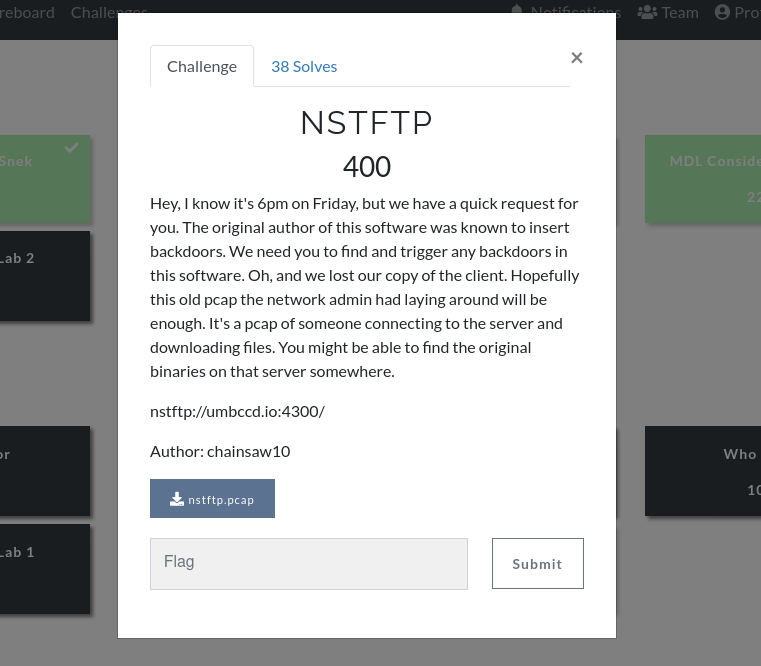

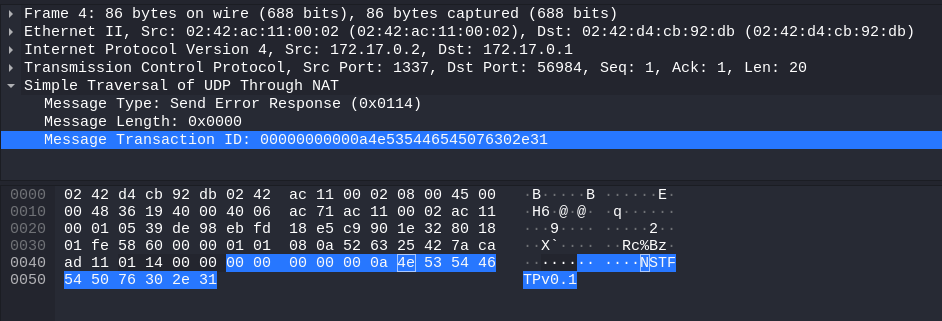

First, how does the client say “hello” to the server?

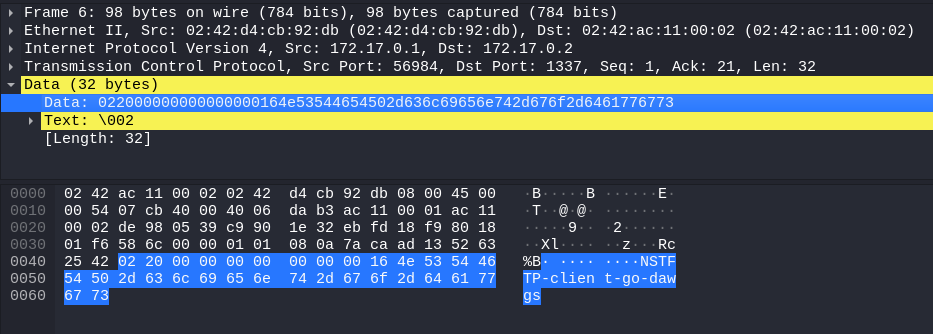

Inspecting the very first interactions between client/server, we could find this “banner” (NSTFTPv0.1) and “client name” (NSTFTP-client-go-dawgs) being passed in order respectively. Coincidentally, the banner message was parsed by Wireshark as that weird UDP protocol I mentioned before.

Ok, how do we specify server commands?

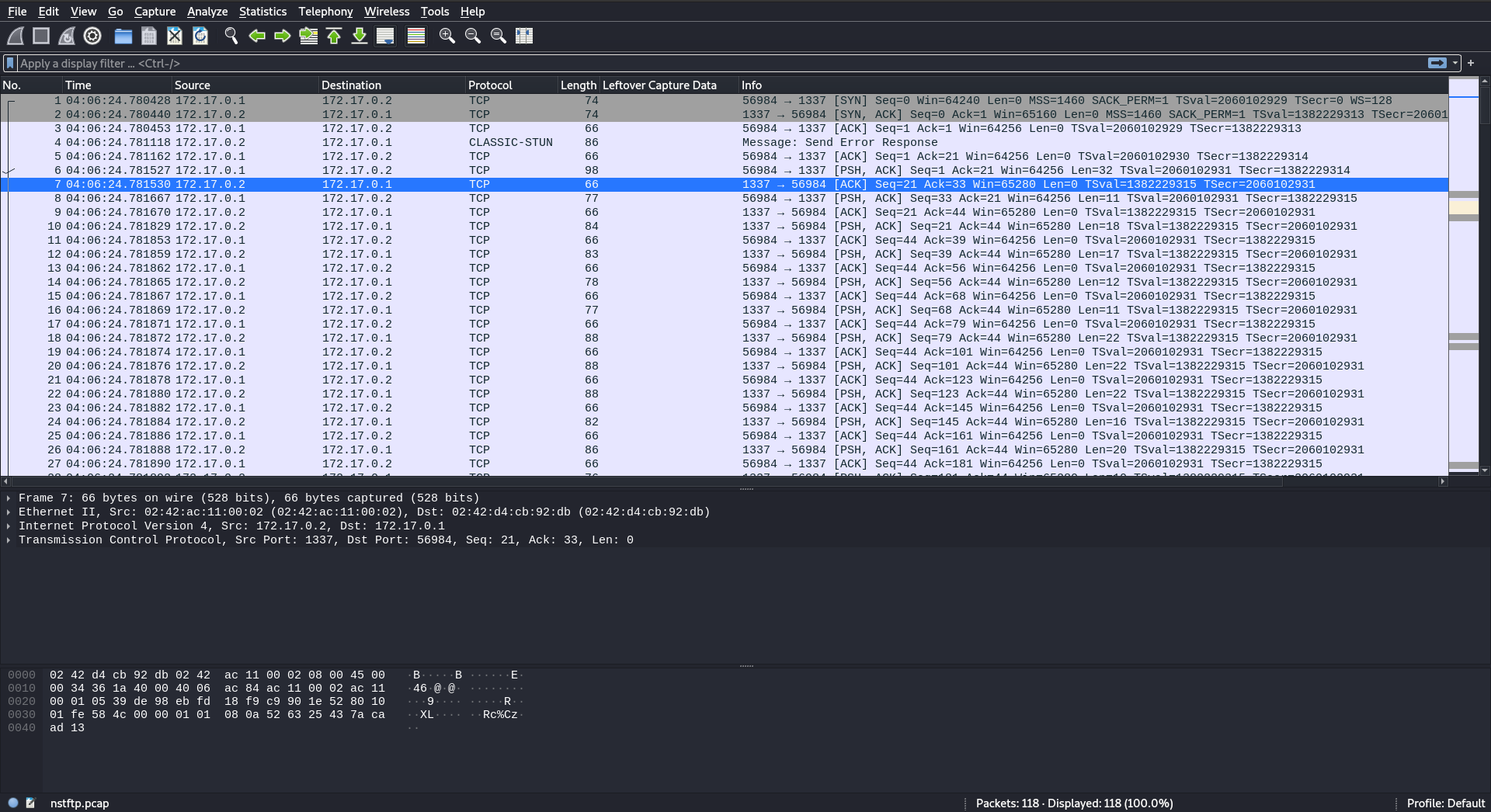

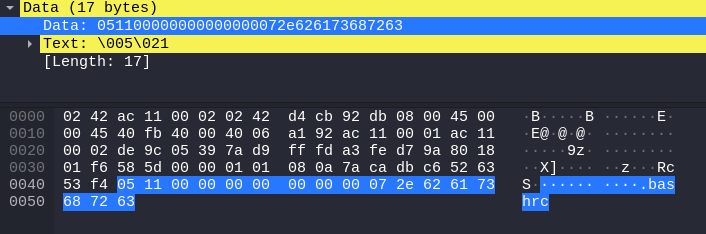

Looking at the first messages sent by the client before getting the file’s names (let’s call it ls) and then an arbitrary file’s contents (which will be called get) I noticed 2 things:

- that the first 2 bytes changed between the 2 commands (

lsandget):03 0bfor thels,05 14and05 12for theget README.txtandget .profile - that there’s some null byte (

00) padding that’s being repeated on every client/server message between the first 2 bytes and the ASCII text parts

So now we can make an educated guess that the first byte is related to the FTP command that we want to execute! (03 for ls and 05 for get)

Continuing, how many bytes per message is the client/server expecting?

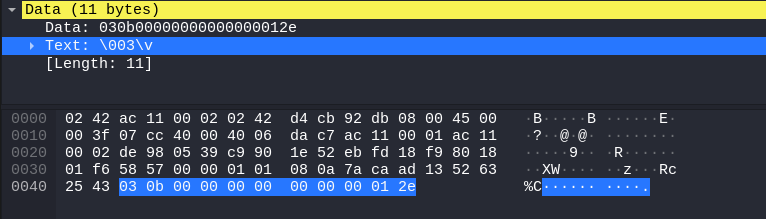

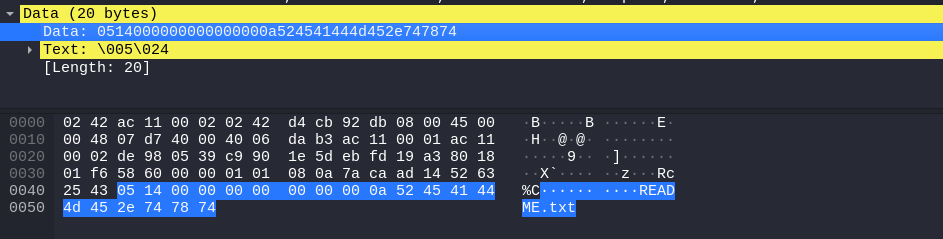

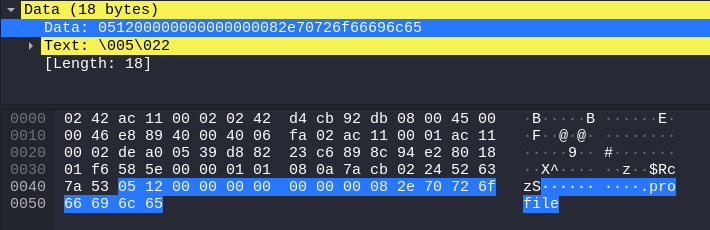

Looking at the previous packet’s images and some server replies, we know that these messages have a dynamic size (the first image shows a size of 11 bytes, then 20 bytes and finally 18 bytes), so the size per packet must be inside that same message, right? as there’s no more extra information between the request packet and response packets.

Aha! Now we’re onto something… Remember the raw data string 03 0b 00 00... which is 11 bytes long, 05 14 00 00... which is 20 bytes long and 05 12 00 00... being 18 bytes? Well, the second byte for every one of these strings contains the total length of the message!

0x0b=>110x12=>180x14=>20

And this is also applied to messages sent from the server to the client! (only on the ls version tho, more on that later).

So that solves another mistery… and if you have a sharp vision and payed close attention to every image i’ve posted so far, you may have noticed that there’s 1 extra byte before every ASCII string in all messages being sent between the client and server! (and viceversa)

For instance, with one of the messages from server to client after a ls:

|

|

only the last 8 bytes correspond to the string .profile, which means… 08, the byte before the start of the string contains the size of the ASCII string! This “educated guess” made me look into other messages for confirmation, and it really was like that.

Another example from server to client after a ls:

|

|

Where 2e 2e is .., and 02 again being the size of that string, but also 0c (12) being the total size of the data packet.

Now going even further, I tried to think if those null bytes (padding) were packed in a common certain way to better understand their purpose. 0c 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 02 is exactly 9 bytes long, which can’t be packed in a 64-bit int, however, 0c 00 00 00 and 00 00 00 02 can be packed into 32-bit ints (in little-endian and big-endian order, respectively).

But, notice something? that’s right, the remaining null byte (00) sits alone in-between those 2, 32-bit ints as a separator (that’s the best explanation I could come with).

What’s missing?

Now, the only things we haven’t really explained from the .pcap is the response method from server to client when the client requests an arbitrary file’s contents and also the “how do we know the server stopped sending files” after the client sends a ls, so let’s start with that!

How do we know the server stopped sending files in a ls?

After a ls, the server sends one data packet per file in the given directory (which btw, supports arguments - you can give an arbitrary dir to ls), but ends the dir listing with the following data packet:

|

|

Which already follows our previous deductions, as the size for the ASCII string is now 0 (00 00 00 00), with nothing following after it, and with the total size of 10 (0a 00 00 00). Now, what is the first byte (04) for? that’s something we can’t really tell now, until we actually interact with the server, so it doesn’t matter to us right now (perhaps it could be a response message?).

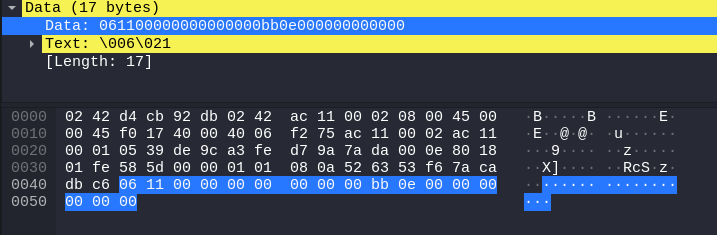

How does the client know the total size of the retrieved file in a get?

As the subtitle implies, we now have to inspect in detail the client/server file requesting interaction.

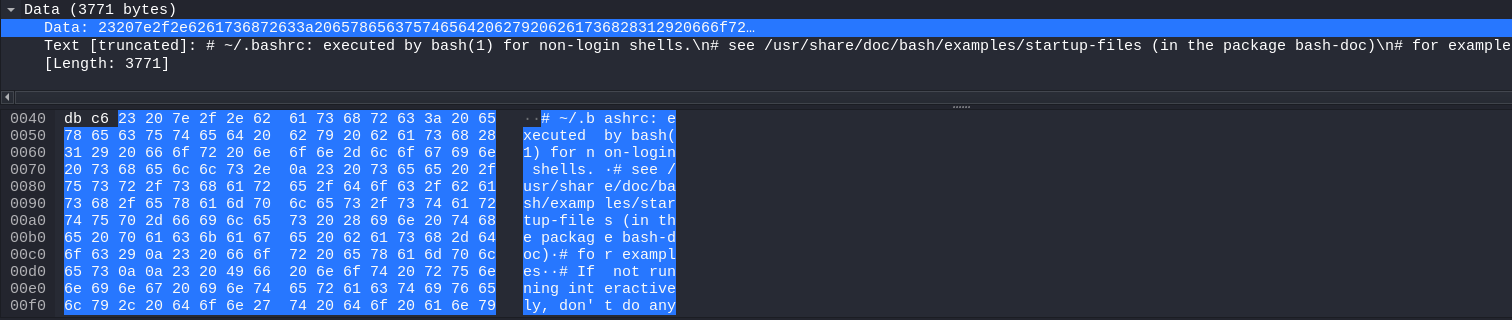

When the client asks for a file’s contents, the server replies in the following way:

Now, the middle-step is surely the interesting one! We can ignore the first byte (06) as it’s repeated on every other response message just as the 04 with the ls command, and the second byte is still the total message length (0x11=>17), however, the next bytes should be the total size of the file we are requesting (otherwise we wouldn’t know how many bytes to wait for in our client).

In this occassion, the total size is 3771 bytes, which translates to bb 0e 00 00 in little-endian and to 00 00 0e bb in big-endian for 32-bit ints.

With the following data packet:

|

|

Which version fits inside this packet? That’s right, the little-endian version (bb 0e 00 00), but this time fitting this 32-bit int at the end of the packet leave us with some extra null bytes before and after the 32-bit int (... 00 |bb 0e 00 00| 00...), which doesn’t seem ok, don’t you think?

Thinking bigger, the 32-bit ints (for the total message size and total file size) + the extra paddings fits perfectly as 2, 64-bit ints in little-endian, which makes a lot of sense, as some files could be bigger than the limit imposed by a 32-bit int (~4 GB), leaving us with: 06 |11 00 00 00 00 00 00 00| |bb 0e 00 00 00 00 00 00|.

Now we know how to handle the server’s response to a file request, yay!

Are we done yet?

Not yet, little grasshopper, there’s another “quirk” that we need to take account of for our client program: every time the server sends us a raw file after requesting it with the get command it “closes” the connection (contrary to the “hello phase”), that is, it stops accepting commands as it did before, so we need to re-start the “hello phase” from the beginning, which consisted in receiving the “banner” (coming from the server) and then sending our client name.

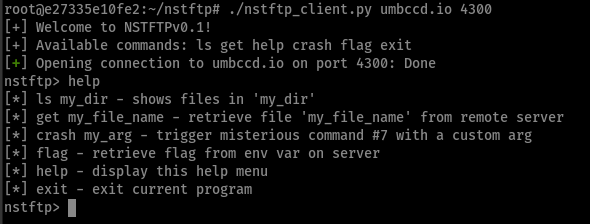

Making The NSTFTP Client

This part consisted of mainly programming in Python taking advantage of pwntools lib (for the sockets and int packing) and using re (for the regexes) for command parsing from the user (the author likes robustness in his programs), but you are free to do and use whatever language or library you like. The only things it needs to take into account are the protocol specifications when talking with the server!

Retrieving Files

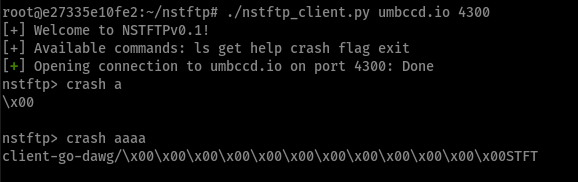

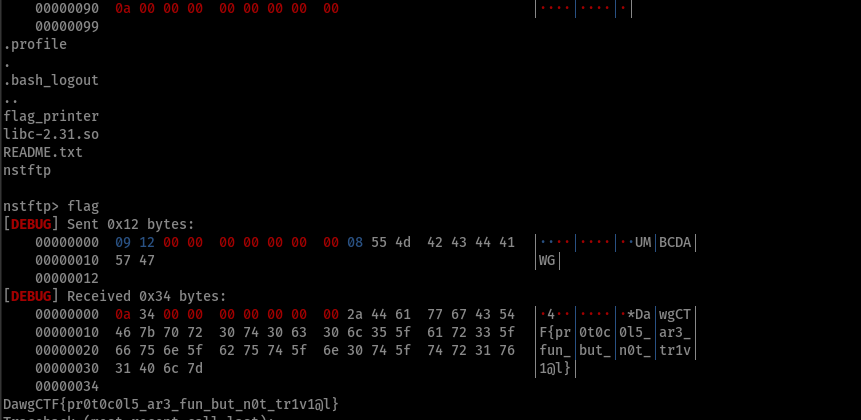

After running a ls ./, we could finally see the “oh-so-promising” files along with the flag_printer program. This is it!… right?

NO!

Turns out, the flag_printer program was just something you would use in the pwn related to this challenge (NSTFTPwn), a challenge that required you to have the ftp client first to actually be able to retrieve the file to pwn (the nstftp server).

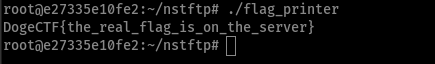

As you can see, the main function consists only on calling that get_flag function and depending on the latter’s success it either prints the dummy flag (DogeCTF{the_real_flag_is_on_the_server}) or the real one (there’s an implicit branching and assignment through the cmove rdi, rax). The get_flag function justs checks if it can read /root/pwnflag and returns its contents: if it fails it returns NULL, otherwise returns the pointer to the buffer with the contents of the file.

But… whatever, we now knew the backdoor would be probably a command or secret phrase that you could send to the nstftp server in order to gain access to some secret (the flag), which would mean… adding another command to our client!

The Hunt for The Backdoor Starts

Now this is when the real reversing started. I started with the classic strings to give myself an idea of what we could be looking at, and these strings stood out from any others:

|

|

FLAG, UMBCDAWG and DogeCTF{real_flag_is_on_the_server} were interesting as UMBC is the name of the university, and the others are straight up flags, so probably where those were, something interesting would be happening.

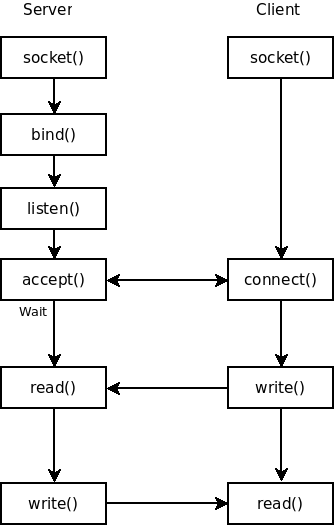

Besides this, I suspected that finding the piece of code that dealt with commands from the client would probably lead us to where the backdoor was, so I started digging the fastest way possible through the generic “web server communication” boilerplate code trying to gain a deeper understanding of the workflow and if some secret “shazam” password would be required somewhere.

Figure credit to Ahmet 1

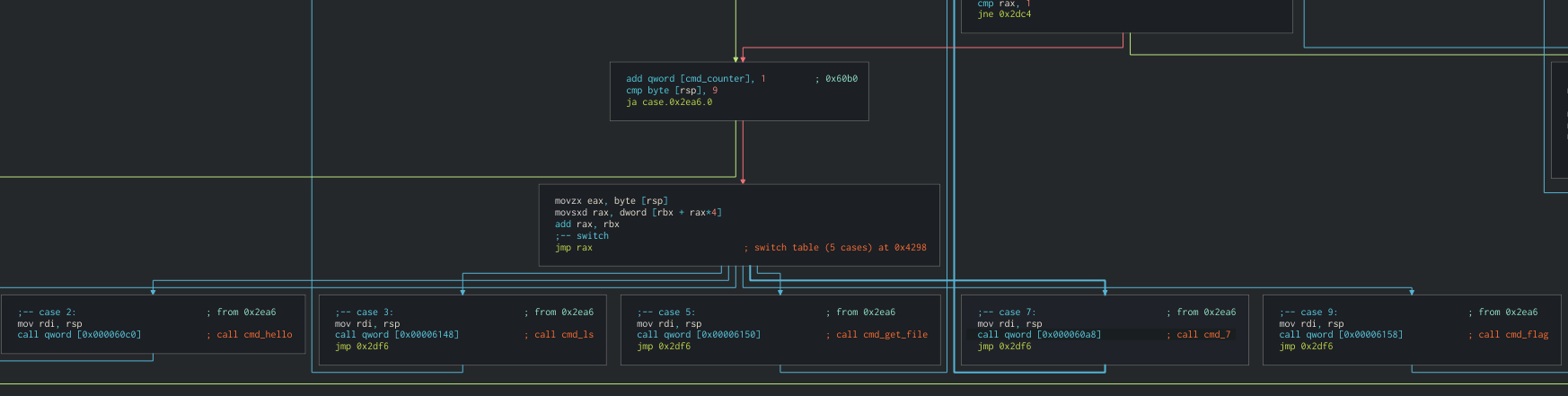

After a while I found the command handler function at 0x00002d0d, where I got surprised as there were more commands than just the 2 we analyzed in the .pcap on a switch table, which dispatched the RIP to other functions as indirect calls. We’ll call this function handle_cases.

I could map the first 2 commands we were talking about at the beginning for ls and get: they even had the same int for each one on the switch table! (03 and 05). However, command 2, 7 and 9 were still a mistery, so I followed their indirect calls and defined functions there and found some interesting stuff:

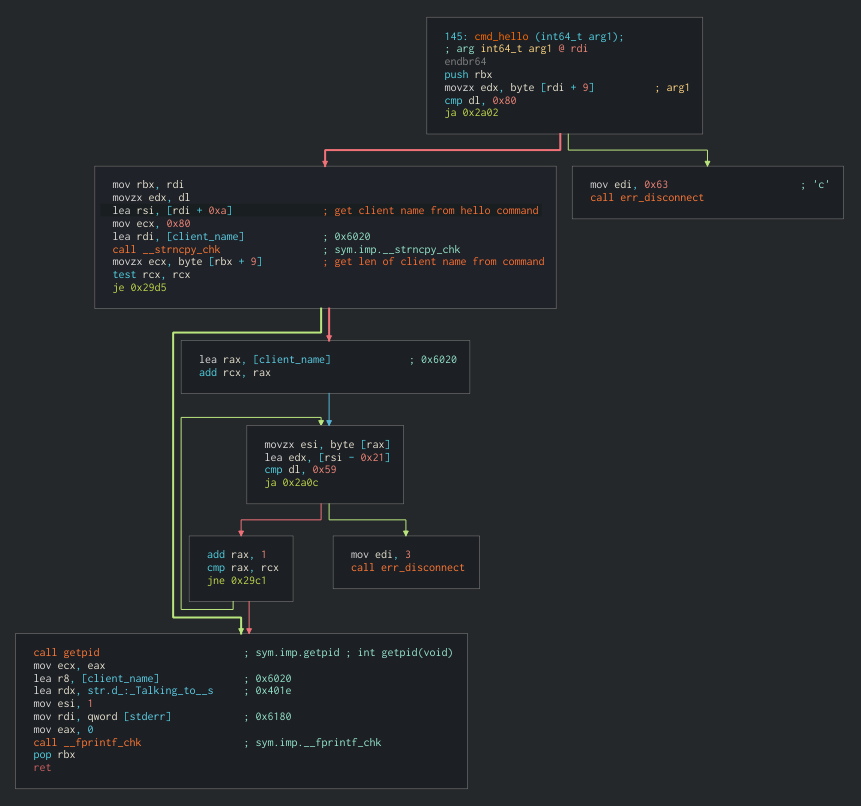

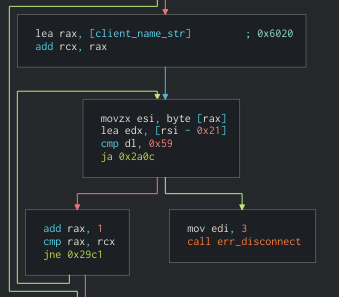

This function was run by the server every time a connection was made from any client, and it printed the client name (NSTFTP-client-go-dawgs) inside the string Talking to %s. Also, it made checks to the client name before actually accepting a full connection, like checking the client name only contained chars below 0x7a (in the condition 0x59 < rsi - 0x21). This meant that the client name could be almost arbitrary as long as it complied with these constraints.

The var holding the client name was a global var and the server would set it at the start of a conversation between the client and server (command 2 is the “hello” command!).

For command 7 I didn’t actually try to understand it in-depth, as the most promising function for the flag was already found before this one and the CTF clock was still ticking.

An interesting thing about command 7 is that it leaked memory to the client in purpose when triggered (I figured it’s probably for the pwn version of this challenge):

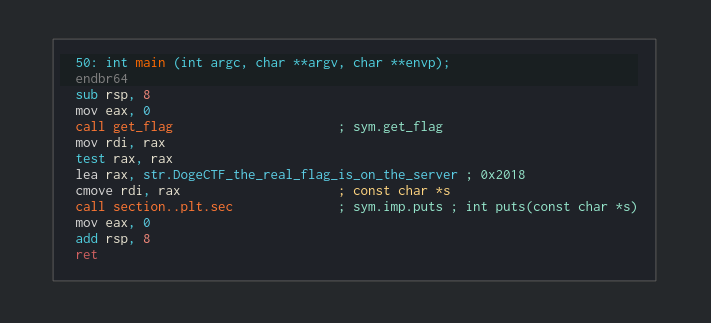

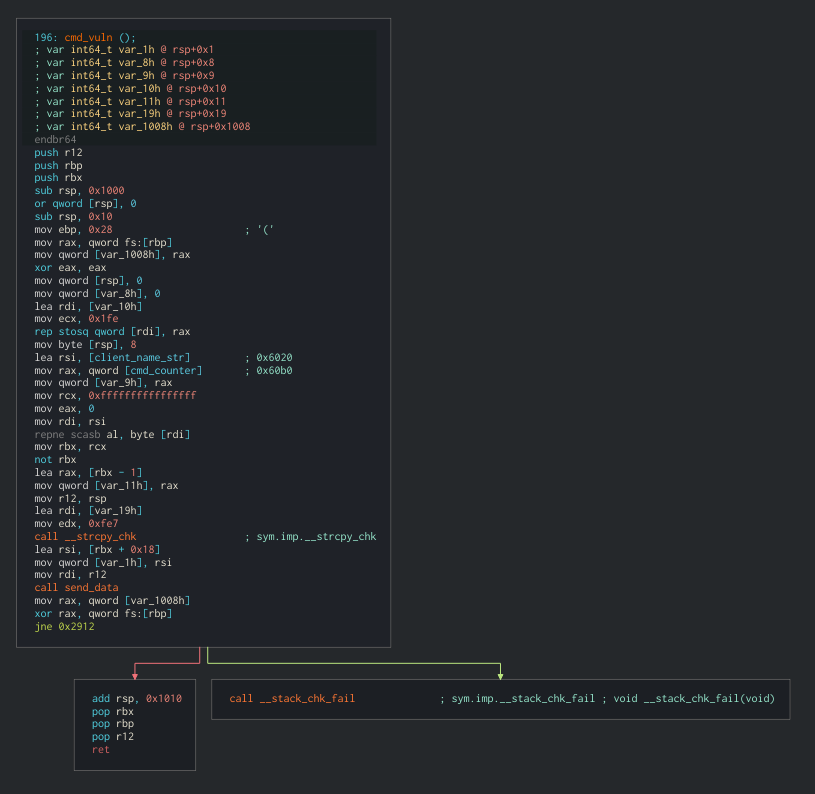

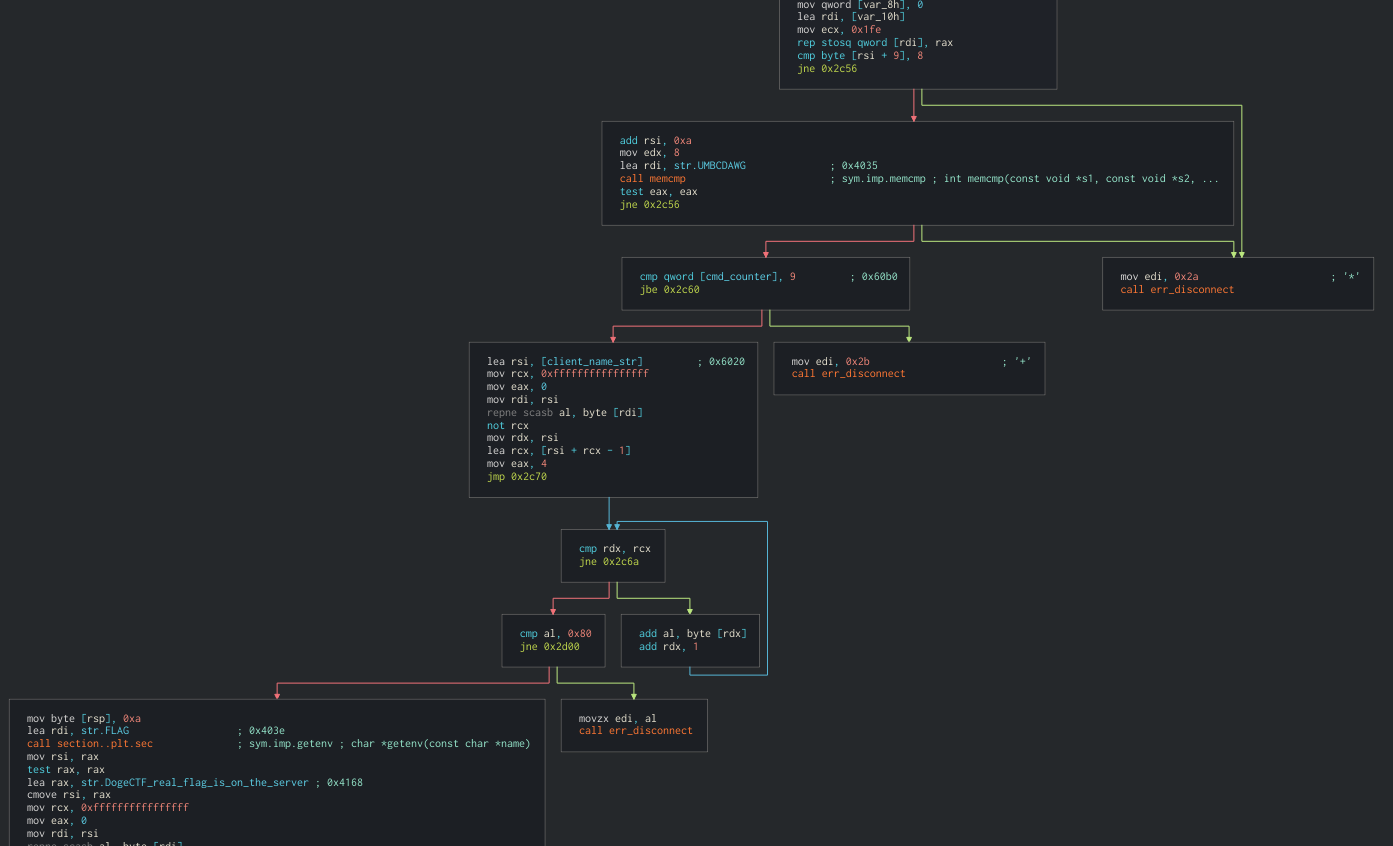

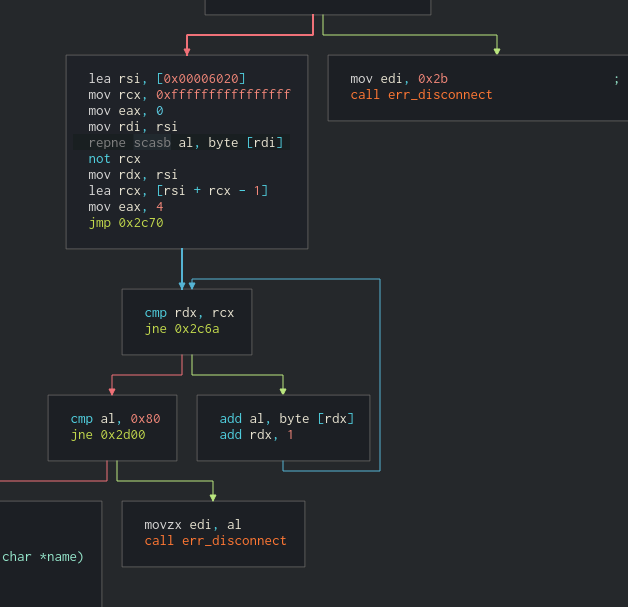

Passing to command 9, the real backdoor was found. It required the string we found before (UMBCDAWG) as an argument before passing to other checks, to finally spill the flag which would be stored on the server as an env var (called FLAG):

Now we were really close to getting the flag!… Sadly my lack of sleep here really started to kick in and with it my focus vanished too, but luckily, my teammate f4d3 was still awake and helped me realize some things:

-

The backdoor function also checked the number of executed commands, that is, every time you called a command on the server, it would increase a global counter (for that connection), and to advance to the flag printing this counter was required to be greater than 8.

-

After that check, the sum of every char (plus 4) in the client name would be checked against a fixed “magic” number (

0x80=>128) in order to print the flag.

Note that as the client name counter starts as a 4 (mov eax, 4), 124 would be the correct “magic” number for a crafted client.

(Again, massive thanks to f4d3 here as he found one working example for the client name that solved this checks when my brain just stopped working)

Keys to the Backdoor (Recap)

So what do we need now to get our flag?

- We need to call any non-crashing command (like

ls) at least 8 times before calling theflagcommand (cmd 9). - The argument for command 9 has to be

UMBCDAWG. - The client name needs to be composed of printable bytes only and the sum of the chars (modulo 256) needs to be equal to 124.

One client name that solves 3. is NSTFTP-client-go-aaaa=, another is GGGi>, but you can craft any other that follows those constraints. Check out the tool I made to craft 5-char-long valid client names here.

After knowing this, getting the flag was as trivial as changing 1 line in the client code and sending the required commands.

DawgCTF{pr0t0c0l5_ar3_fun_but_n0t_tr1v1@l}