OhMyRE!

Summary

The RE program from this challenge runs in a remote server and requires a password and username to output the flag. A valid password for the program is one that meets certain criteria or constraints (specific length, subsequences that are equal to a constant, etc), and thus consists of a combinatory problem with many different passwords that would match. The username is a unique hardcoded string that goes through a simple linear transformation routine.

This problem category is part of the SMT and CSP family of problems, and are commonly found in reverse engineering challenges as sub-problems. Solving these can prove to be quite hard regarding computing and runtime resources. That’s why SAT/SMT/CSP engines can be used in order to solve these sub-problems in an efficient and flexible manner.

The following blog post goes through the different steps to solve this specific challenge and shows one specific approach using Z31, the theorem prover from Microsoft Research.

Note: As this challenge only got 2 solves, I tried to go a little verbose in this post to explain some things in detail. If you’re an experienced reverse engineer just skip to part 2 for the z3 script.

Overview

Oh My RE! Me pidieron completar esto con mis datos, pero no funciona :(

– chall description

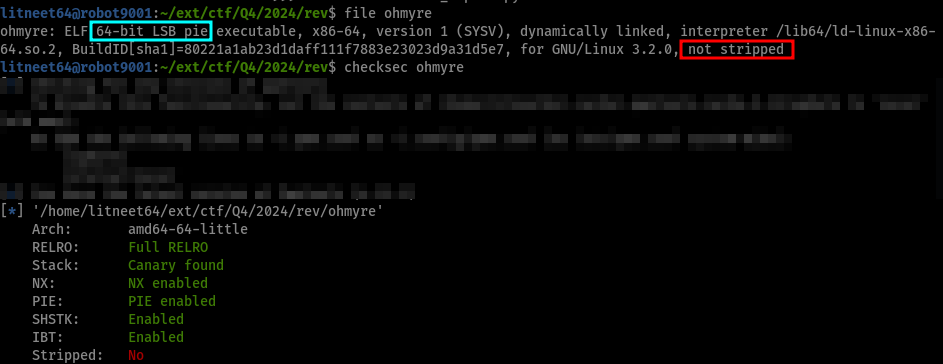

This challenge started with a simple ELF binary for x86 64-bits that is not stripped and with all modern protections enabled.

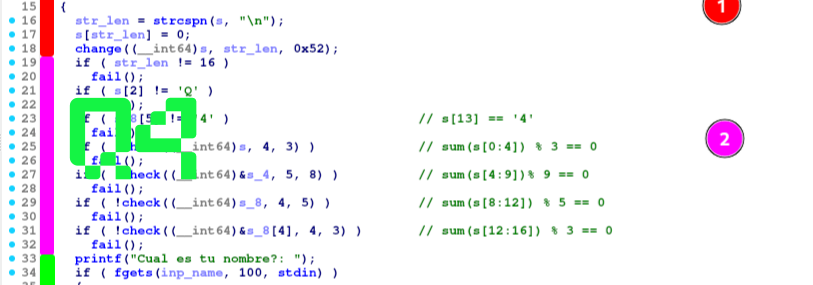

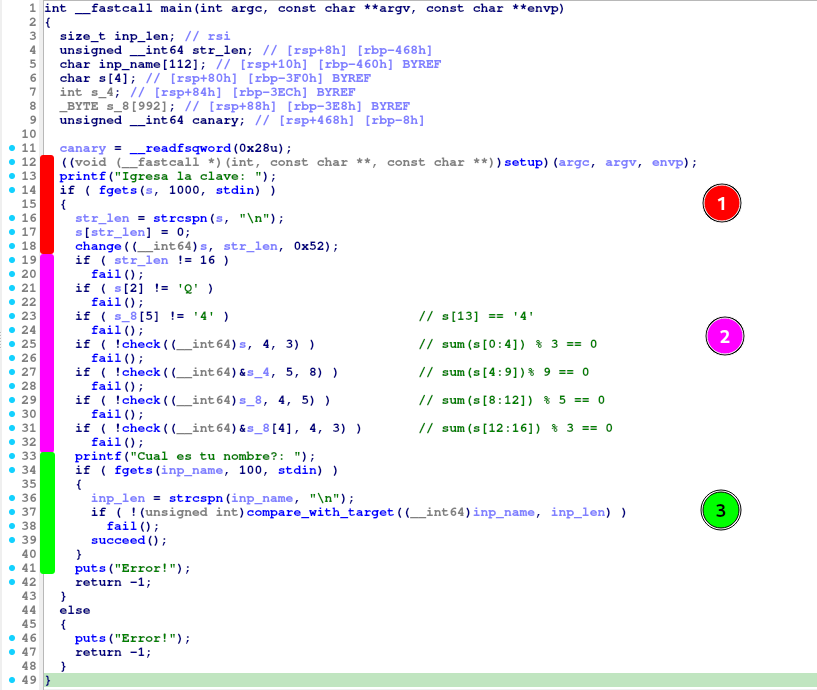

Looking at the main function in IDA’s decompiler we can go fairly quickly through the major parts of the program and roughly divide it in 3 blocks.

Tip: Always remember to comment chunks of code and name your variables in IDA/Ghidra/Binja!

Part 2 contains the most interesting part of the challenge. Rest are standard functionalities in CrackMe’s.

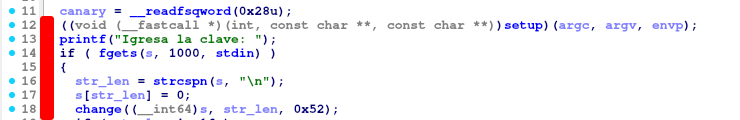

I. Transform Password Input

Consists in:

- Unbuffering

stdin,stdoutandstderronsetup()usingsetvbuf()(irrelevant to the challenge) - Getting 1000 bytes of input from the user and store it to

s(no funny BOF business with this buffer). Note thatfgets()reads until it finds either a null-byte (\x00) or a newline (\n,\x0a) - Get length of user input using

strcspn()(index in buffer for char\n) and null-terminate string - Perform some transformation over the user input in function

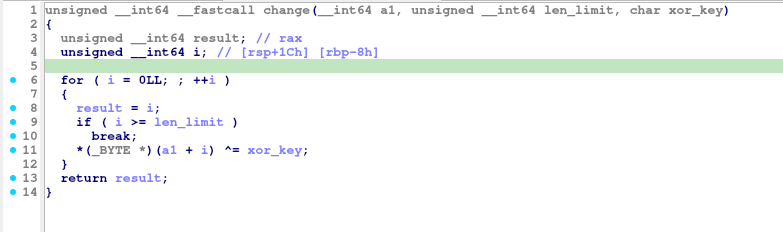

changeusing and a hardcoded byte (\x52) and the string length

change()

Looking at it closely under any decompiler after renaming vars, one can realize that it’s just a function that performs a xor operation byte-to-byte over the input string (s) using the given hardcoded parameter (xor_key = 0x52), stopping after reaching the string length.

That for-loop can be rewritten as the following C code:

|

|

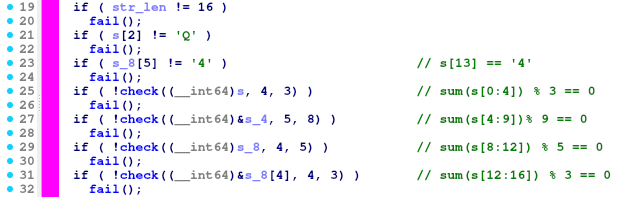

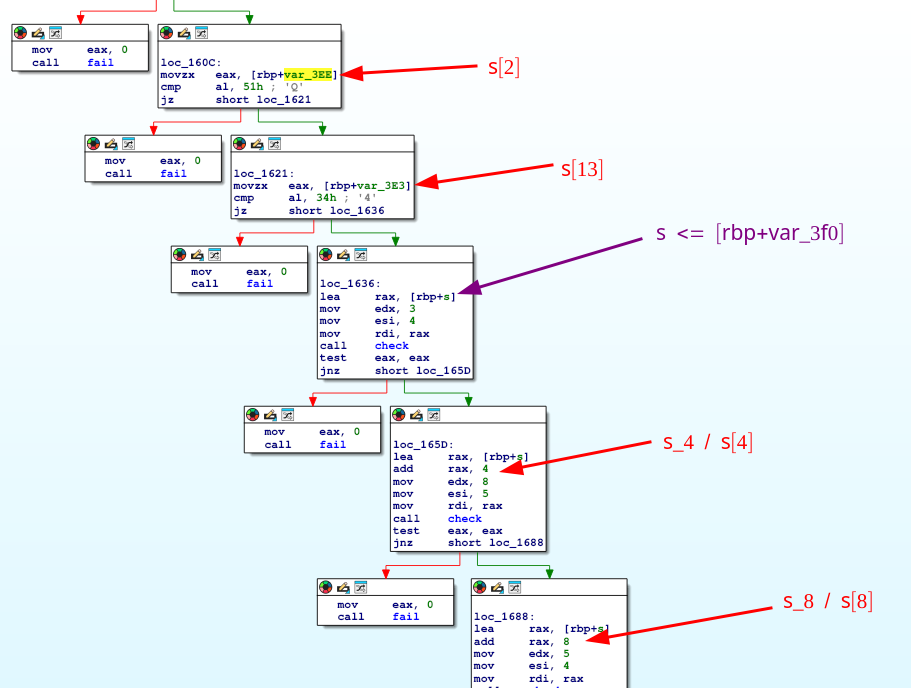

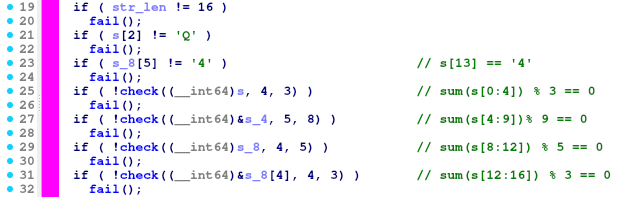

II. Password Condition Check

As if my comments are not spoiler-ish enough… let’s break down the main dish on the menu.

fail()

The condition we want to avoid. Just prints a custom message to the screen and finishes the program execution through exit.

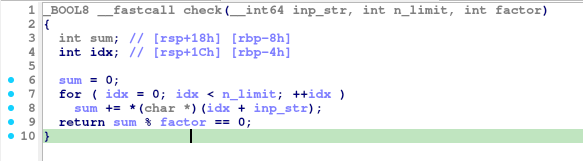

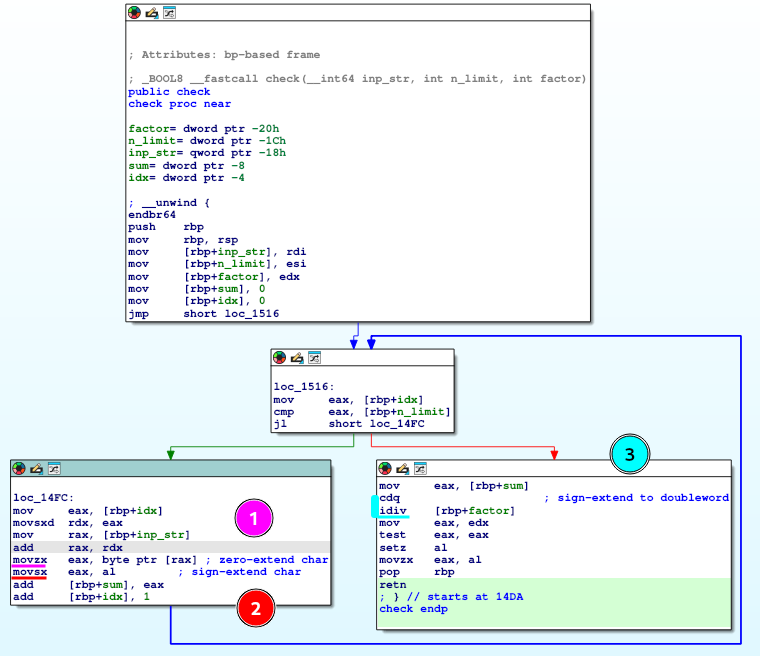

check()

After some renaming, the decompiled function looks simple enough: go char by char through some length (n_limit) of the input string, adding the raw numerical values of these chars to a sum variable. Finally, check if the sum is a multiple of a factor (n % factor == 0), passed as an argument.

However this has some caveats and it’s the reason why I encourage new reversers to not just depend only on the decompiler, but to check the ASM and other sources of information from the disassembler too.

sumis a 4-byte signed integer, and chars are only 1-byte. So how is the up-casting for the chars being done at the processor level?- How’s

sumandfactorhandled for division and remaindering at the processor level?

- Shows that the char (1-byte) from our input string is transformed into a 4-byte unsigned integer via zero-extending the char value (repeating zeros over the 24 most-significant bits) and storing it to

eax(4-byte register). This is done throughmovzx. E.g.0x61 => 0x00000061. - Now, get the lowest byte from

eax(our original char) and sign-extend it back toeax(repeating ones over the 24 most-significant bits). This is done throughmovsx. E.g.0x61 => 0xffffff61. sum(a 4-byte signed int) is converted to a 8-byte long (quadword) usingcdq(convert doubleword to quadword) with sign-extension. Then theidivinstruction is used to divide a signed long withfactorbeing the divisor, with the results being the quotient ineaxand remainder inedx.

Why is this relevant?

Because sum will wrap-around over and over again until settling in a value that will be handled as a signed int. Very different from just adding 1-byte chars as unsigned ints and then checking for multiplicity.

Not over yet

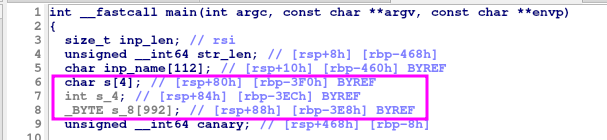

Another thing to take into consideration now that we know how check() works, is that the decompiler is being tricked to show the input string (s) at different indexes (s[4] and s[8]) as other variables.

I named them as s_4 = &s[4] and s_8 = &s[8].

--- title: Memory representation of our variables --- block-beta columns 32 space:4 s_4:4 s_8:24 s:32

Note that the ASM (the ground truth) shows these individual variables that overlap s in the stack, at s[2] and s[13], instead of s[4] and s[8].

SMT, SAT and CSP

Going back to the original image, it should now become apparent that I summarized these check conditions in a python-esque way in the comments I left on the IDA decompiler window, for each if-condition.

These can be seen as “constraints” that should be met by the password we supply. A very naive approach would be to bruteforce all possible values for a char (0-255) for the 4-5 char chunks in each check condition, also taking into account that our post-transformation password should follow s[2] == 'Q', s[13] == '4' AND that there should be no null-bytes (\x00) in-between, otherwise fgets would stop ingesting our input.

However, the search space for that would quickly become unmanageable if the password length increases (in an hypothetical program that specifies password_len == n) or if the chunk length gets increased too, which would mean a longer runtime in order to get one working solution. E.g. the naive approach would have you calculating $256^4 = 2^{32}$ possible combinations for one 4-char chunk.

Besides that, writing a program that solves that small feat through bruteforce, that also has to be drastically changed through each challenge variation does seem really unpractical, boring and dull to program. Implementing a heuristic-based search algorithm2 would be a more flexible and smarter approach, but still lengthy and error-prone to do for yourself each time.

![]()

Figure credits goes to3

That’s how CSP and SAT/SMT solvers get introduced for tackling this family of problems. Note that they still make use of heuristic-based searches underneath, however we only have to worry about understanding the problem, modeling it (partly or completely) and then just translating it to a programming language.

One of my favorites is Z31 from Microsoft, which is the one I usually use for small tasks through the python bindings. Another one is SAGE4, but it’s complete enough and works for mathematical analysis too. Other instrumentation frameworks for symbolic execution, similar to Z3, that can also perform concolic execution, taint analysis and more advanced stuff are KLEE5, Triton6 and one of the most known in the CTF scene: Angr7 (most of these still use Z3 under-the-hood).

Z3 Script

Anyway, here goes my python-3 script for generating one of the many possible passwords that satisfy the constraints for this challenge.

|

|

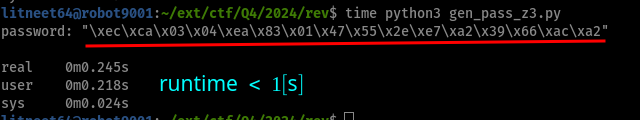

Seeing it in action, it took $\approx1/5$ of a second to get one valid solution for the password.

III. Check Username Input and Get Flag

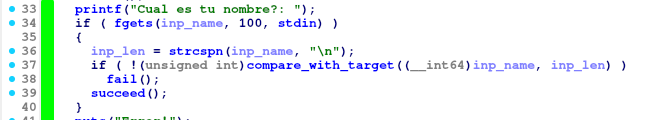

After progressing from the password check, the program asks for a 100-byte long username using fgets, calculates the username length through the same strcspn method as before, and then evaluates the username through the return value of the function compare_with_target(). If the ret value is 1, then the flag will be printed through succeed().

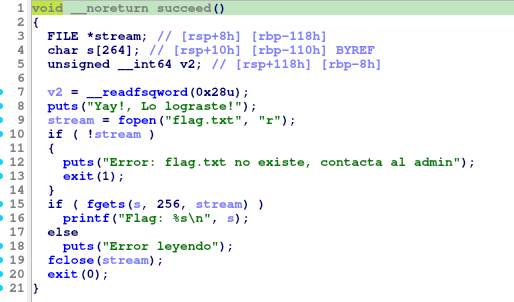

succeed()

Just prints out the contents of the file flag.txt.

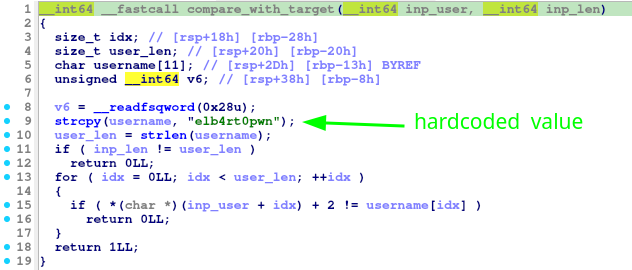

compare_with_target()

Does a sanity check in length vs the expected, harcoded username, and then goes through the given username input string, while comparing your input in a byte-for-byte fashion with the hardcoded correct username with a small extra: it adds the char 0x02 to each char of your input before check.

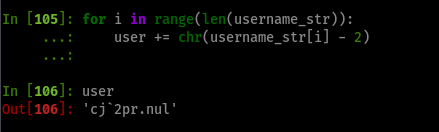

A simple function in a python interpreter is enough for doing the inverse operation in order to get the expected username.

Username Generation - Code Snippet

A small script that contains the next lines can do the trick.

|

|

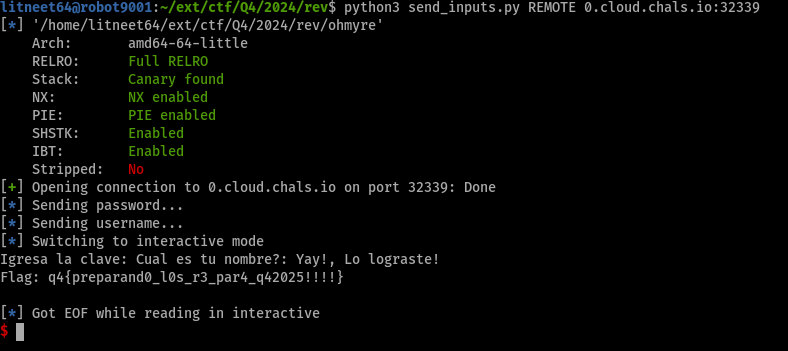

Getting the Flag

Then, sending one of the many valid 16-byte-long passwords along with the transformed username using your favorite python library (e.g. pwntools, socket) will get you the flag.

|

|

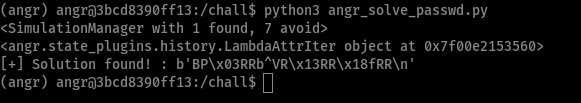

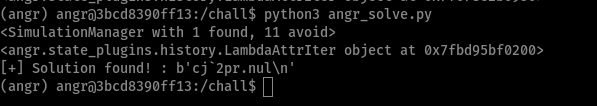

Extra: Angr

As a short bonus for this post, I tried to solve this challenge after the CTF using Angr with the less possible amount of information from reverse engineering the program. Turns out, I couldn’t make Angr get a solution for both symbolic inputs from stdin on the same run, but they can be found using separate states that start and end from different addresses: one that stops before the 2nd call to fgets and one that starts from there until reaching the winning function. Also, I had to manually set the BitVectorSymbol length for the password (to 16 bytes), as fgets reads 1000 bytes from stdin and thus my Angr script ran some hours before I killed it.

So the minimum of RE required to make a script with Angr for this problem should be:

- Get the max length for the secret (e.g. password, username)

- Get the address where you want to start (e.g.

mainfunction), along with the address of the end of a certain state (e.g. before the 2ndfgets) to solve for one secret. - Also include addresses for functions to avoid (saves time and resources to the sym engine as those paths are instantly pruned), such as

fail()

The script that achieves this is left as an exercise for the reader! (RTBM hehe)

-

like backtracking. ↩︎

-

Predicting process performance: A white‐box approach based on process models - Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Backtracking-algorithm-taken-from-47_fig2_33204163 ↩︎