IQA Website Link Farm: what hides behind an innocent frying-pan image

Intro

Some days ago I got a tip from a close friend that something fishy was going on with the Chemical and Environmental Engineering (IQA - on spanish) website from a Facebook post on one of our Uni groups (OtakUSM), so naturally I was eager to know in-depth what happened and what was the purpose of this new (for me) attack. Join me in this journey of dissecting and then recognizing a nowadays very common type of attack scheme and Black Hat SEO techniques.

- initial “tip”

First Clues

Two days after receiving that tip I tried to reach the web page but all I got was a blank, empty page on the index page, no japanese words nor kanji/hiragana to be found, and making the same Google query as the one from the tip didn’t show any japanese words on the site’s description neither. Seemed like their sysadmins were kind-of fast on noticing and “acting” on it…

Whatever, let’s search if this wasn’t just a cheap trick.

- Security Trails results

The Passive DNS records showed no evidence that the domain was hijacked recently, and the SSL certificate handed by the server was the same as the public known one from Censys’ Certificate Transparency database:

- Censys.io results

This looked more like an abandoned site than a defaced one. There wasn’t a sign that this was hacked recently, but neither a sign that this was a healthy site. Even a quick dir-bruteforcing showed that wp-admin/ was still up and working…

Well, this was still not over as luckily, web caches are a thing 🥸.

Going Back in Time

Searching on The Wayback Machine yielded no relevant results, just some really old views of how the IQA website was 4 years ago, and a 2019 saved version that didn’t load… great.

- Wayback Machine results

Trying some luck with the Google Cache (which just caches the most recent page of a given URL) got me something more to play with:

- Google Cache results

Aha! Now… what’s this? 🧐

Back 2 Basics

Thanks to Google for another useful feature of their translator!

Using Google’s URL Translator feature I just passed the link to it from Japanese to English to get a grasp of the meaning of this:

- Google Cache Translation

Seems like a shop’s website, but with no actual functionality neither scripts. There was no script nor piece of html asking us for our juicy credit card info, neither enticing us to give our name, email or password… hmmmm.

Something I did catch from the HTML was this copyright on the footer. The name of a real (huge) japanese company being used inside the HTML, Softbank Technology Corp., however this was no malicious replica / evil twin of any of their pages so why would this be here? 🤔

- Page footer

Also, the <head> tags of the page had words like New Aluminum Casting Wooden Steak Bread Small-Grill Bread (in japanese of course), even on the keywords head term.

I tried looking at the requests this page made, in order to catch something like a web beacon, or perhaps a missing asset that couldn’t load (like css or a previously malicious js script that’s now disabled or irretrievable).

- Sent requests

No luck, just 500 error messages while mainly trying to retrieve images, meaning the cache we were seeing didn’t include everything that was on the compromised website, and searching for those same images on the IQA server threw a 404 error… But wait, an image coming from shop[.]r10s[.]jp?

That was the only image left that was visible on the cached version: the frying pan, and the request was made to tshop[.]r10s[.]jp, another subdomain of r10s[.]jp, before being redirected to the latter. Also, notice the webserver path? it’s /chubo-kitchen/cabinet/flypan/5709901.png, as if it came from a shop with multiple products 🤔.

- Just a frying pan

This “orphaned” resource can surely tell us something, so let’s take advantage of this very small foot-grip making a reverse search to check its origins and get a better idea of what’s happening:

- TinEye, no results

- Google Reverse Image Search

Bingo, the exact same image was found on our site (IQA website) as a top result, and another similar image showed on Amazon as a selling product. But more importantly, the other websites, which had the exact same image (with same proportions, 1200x1200) as the IQA result, presented the same behaviour as our initial tip showed!

Following those links led us to:

- MyMagic 404 page

Seemed like the website’s owners realized they were compromised and managed to clean it (the results from the reverse image search weren’t up to date), and their page showed no requests to any other “weird” domain like our cached version. Also /chubo-kitchen/10364fexc5709901 appeared again (on the host url), but with some modifications to the version from before.

The main site’s page showed us that this was a legitimate, still used website, unlike our case.

- Magic: Malasysian Global Innovation & Creativity Centre

We got lucky with the other website 🧐

- Turbochef, in-page URLs

Note the host url (/chubo-kitchen/1004sewx5709901) and the requests, which showed again that a request was made to tshop[.]r10s[.]jp and then got redirected to shop[.]r10s[.]jp to get the frying pan image. But this time a new external domain appeared on the requests, girlfriend[.]kari[.]jp. Sadly, those requests just hanged there, getting no replies from it to this site.

The main page for Turbochef showed again that this was again another “big shot” website that was still operational, but with no signs of compromise showing on the front:

- Turbochef main page

Another one of our list of sites that used the frying pan image was this polish website:

- Polishbrief

However this one was a new variant, it only showed the modified page if you passed some special parameters to the index.php: smsite, smid and smtemp. And again, the main page showed that this was a fairly relevant and used website with no sign of that mess from before.

- Polishbrief main page

What do they have in common?

First I tried searching for common CMS/framework/libraries being used between these 3 sites and ours. WordPress was a common factor between Turbochef and IQA, however the versions used by the 2 differed drastically with no critical CVE found between these.

So the main common things:

- They are high-authority domains/sites.

- Most links on the compromised sites point to the compromised site itself, with every page having lots of “product’s keywords” (grill, waffle machine, rice pot, etc) and links placed randomly on the HTML.

- Only some of the links point to japanese sites but most importantly to

shop[.]r10s[.]jp, which serves the frying pan image.

Going down the rabbit hole

Searching for the original location from which the frying pan was being sold I found Rakuten’s e-commerce site:

- Original frying pan site,

hxxps://item[.]rakuten[.]co[.]jp/hokuashop/4977449564812/

Which coincidentally, was the same owner for the previous domain r10s[.]jp, which btw was only used as a domain to host images (it had no front page and it replied with 1x1 pixel images on every other path):

- Whois info for

r10s[.]jp

Rakuten is a widely known e-commerce and retailing company from Japan, which can be summarized as “the Amazon of Japan”.

What info we got so far from this:

- The manufacturer of these frying pans is Hokuriku Aluminum (Hokua)

- Rakuten sells this product directly on its page

- The keywords placed on the hijacked sites matched some of the words found on the original frying pan page (

Aluminum casting wooden handle steak bread small gas fire, andSteak Frying Pan Grill Pan Grill Aluminum Casting Cast Commercial Professional) - There’re looooots and lots of kitchen utensils and related words (it’s a kitchen utensils shop, duh)

Now, what does this have to do with the previous information? 🥱

Black Hat SEO

Enter the concept of Black Hat SEO (search engine optimization) and its techniques. Basically, it consists of unethical practices to benefit from algorithms used by search engines to get a higher ranking on their search results, “black hat techniques include keyword stuffing, cloaking, and using private link networks.”, and of course, as search engines are frequently evolving, nowadays they can often detect that behaviour and end up penalizing (lower the score) sites engaging in those practices.

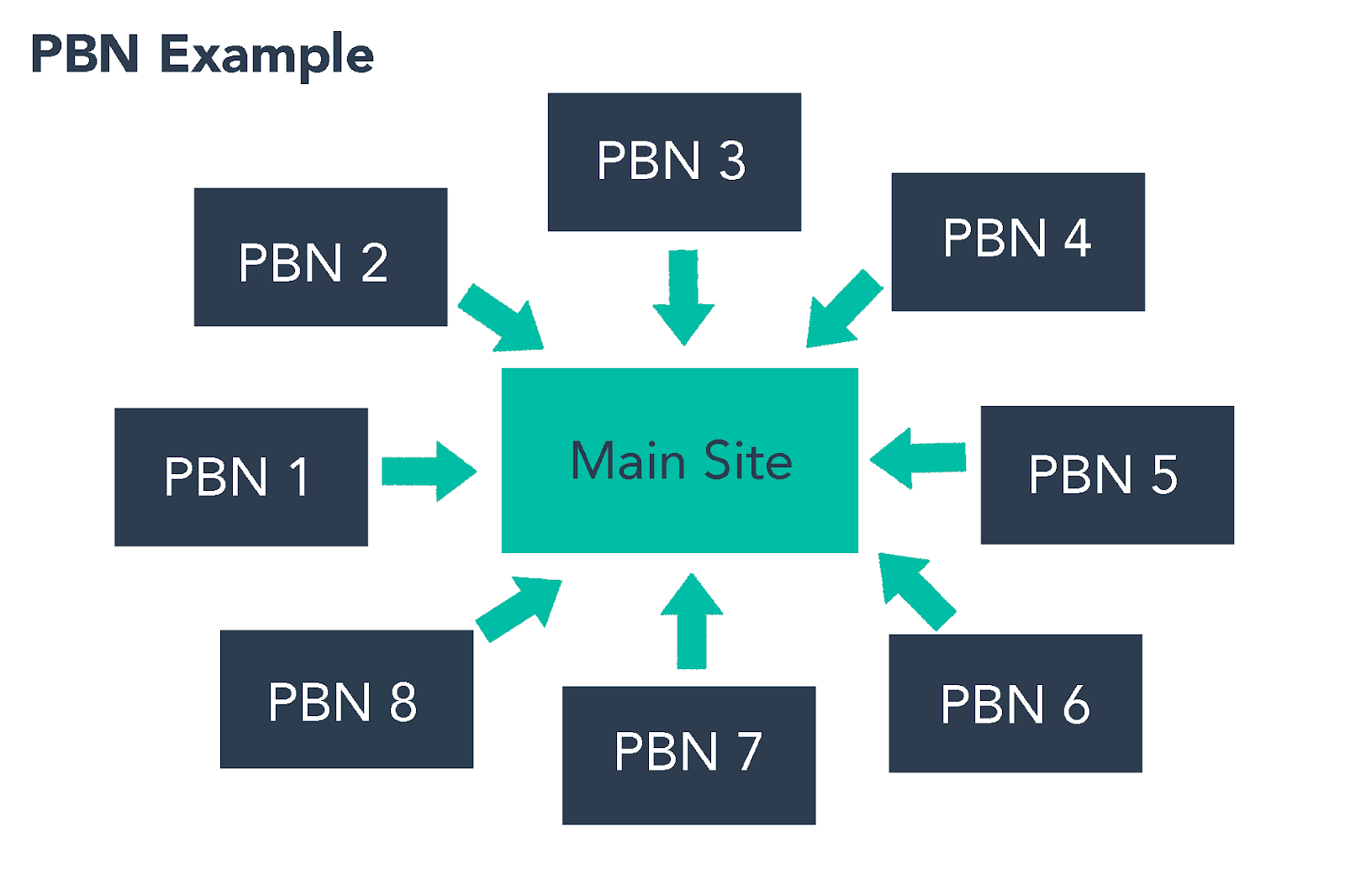

Here the more fitting schemes were “keyword stuffing” and something akin to “link farm” (private blog network):

-

Keyword Stuffing: inserting words on a site (or keywords head tag) with the intent of increasing the chances of appearing on the first results of a query related to the keyword’s topics, however the real content inside the pages has often no relation to those topics at all neither some semantic coherence. Sounds familiar? yup, all those home product’s words being thrown indiscriminately here and there on every hijacked page.

-

Backlink Scheme: inserting links on a site that point to the target website you want to increase their rank, as search engines factor the number of links pointing to a website into its page score, giving higher scores to sites with lots of links pointing to them, as long as they’re naturally made and not artificial.

-

Private Blog Network: a type of backlinking scheme, where one or more target entities own a group of seemingly unrelated blog websites and make them point back to the target entities. Generally those blogs are not inter-related as to not get the complete network easily flagged and identified by search engines. In our case, the backlinks point to a domain belonging to Rakuten (

shop[.]r10s[.]jp).

This coupled with the higher authority of the hijacked sites could lead to a boost on the SEO score given by search engines.

- Private Blog Network, image taken from

https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/black-hat-seo

Perhaps Rakuten is engaged on these shady practices, or maybe they could’ve hired a low-quality, third-party SEO manager (or company) that engaged in this? 🤔

BUT…

Let’s not jump directly into these conclusions, as Black Hat SEO can be a double-edged sword used also by shady competitors looking to lower the score of their competence, via poorly executed Black Hat SEO techniques in order to get their competence identified and penalized to lower their rank on search engine’s results pages.

This makes a little more sense than the previous hypothesis as the often-linked site (which gets an authority boost) is a domain that’s just being used to retrieve images and gifs (shop[.]r10s[.]jp), instead of the main site that’s used for selling products, although reciprocity in links is also factored in for ranking, and the main shopping site points to that image-gif domain too 🤔.

Robots.txt

Another thing that can’t be left out is the existence of some modified sitemaps and robots.txt on the IQA site, showing that the site was actually hosting more similar pages than what could be seen by the cached version, and the robots.txt invited any web crawler (used by search engines) to traverse the whole compromised-version of the website in order to get them factored-in in the ranking score function.

- IQA’s sitemap-1, revealing a lot more of paths with garbage pages

- Modified IQA’s

robots.txt, revealing more “infected” sitemaps poiting to internal pages

Conclusion

Intent

The attacker’s motivation now seems clear, it wasn’t anything specifically targeted to IQA, just the actions of an oportunistic attacker, and the hijacked site wasn’t being used for credential stealing, nor storing/delivering malicious software in order to infect users, but increasing the SEO score of another third-party. That’s something we can tell with medium confidence.

Actors

This is something I can’t really tell with enough confidence, and it’s something the IR team from IQA (if they have one) has to investigate and clarify properly, as I can’t just jump into this kind of accusations without more hard evidence. A more in-depth investigation would also require more hijacked sample sites to not miss anything that could shift the whole narrative.

Entry Point

You can read my hypothesis from below.

Extra: Origin of the Breach

As I mentioned in the beginning, the wp-login.php file was still up and reachable, so I grabbed the version through the ver param passed to one of the CSS files (...css?ver=5.2.7), showing the 5.2.7 version released on June 10 of 2020 (this year).

After getting the WordPress version used by the IQA at the time, I searched for critical CVEs trying to see if this could be the work of a skiddie/automated bot, but no “special” (a.k.a worm-able or zero-click) CVE was found for that version until this day.

- NVD NIST Database Query

(you can read the whole CVE list here)

And an external nmap scan didn’t show anything particularly vulnerable either, the SSH version wasn’t critically vulnerable and the Apache version (whichever they had) being easily pwnable by having a critical vuln was something very unlikely (unless it really qualified for CVE-2020-11984).

There were no remainders nor artifacts from the breach either (like backdoors on a given port, modified service banners, or even the classic signature left by skiddies), however something interesting here was the FortiGate Web Filtering Service on port 8010.

- NMAP scan results

So much for security, huh?

Conclusion

I conjecture that the entrance path was either through weak WordPress credentials (user/password) or via social engineering to someone that managed the platform trough WordPress (perhaps a secretary, a teacher or maybe even a “sysadmin”), as these are very common attack vectors and thus the most likely given the lack of evidence of an obvious critical vuln. Still, all this is a low-confidence hypothesis as it’s coming from an OSINT perspective, which lacks the more precise and technical analysis that can be done from the inside of an org.